MAY 2024 ISSUE

“Architecture must exhibit these three qualities – commodity, firmness, and delight.”

– Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, Architect

Of the three qualities of architecture cited by Vitruvius in the first century BCE, “delight” is the one easiest to understand. It is an aesthetic quality that separates architecture from mere “building”. It is born out in the design phase. “Commodity” is how well the work of architecture performs and how well it serves its intended use. “Firmness” refers to the robustness and appropriateness of the work of architecture’s systems. “Commodity” and “Firmness” are pragmatic qualities. They originate in the design development phase, but are pervasive throughout the construction documents phase.

Architecture differs from other arts in a number of ways, chief among them, in its complexity. In addition to creating their works of art, artists typically finance and construct their works as well. A work of architecture is different. Though designed by the architect, their work is typically neither financed nor constructed by them; rather, it is financed for and by a client, and it is constructed by a builder. This presents a couple of interesting issues. How much deference should the architect give to the owner, or is it, how much deference should the owner give to the architect? And, how does a builder even know how to build the work of architecture, when it was conceived not by the builder, but by the architect?

The answers are simultaneously easy and complex. The architect and owner must come to a common vision, then the vision must be documented in a way that the builder can decipher. The process for making this happen is carried out in the phase of architectural service called Construction Documents, the third of the five phases of service that architects typically provide. In this post we’ll use the dinky House as a case study to better explain this phase. One sidenote: Somewhat unusually, in the case the dinky House, the architect was the owner, or at least half of the owner.

So, what are construction documents? In a nutshell, construction documents are two separate deliverables – construction drawings and a project manual. Basically the drawings are a set of graphic representations of the house in different views and at differing scales, that serves to document the house . The project manual is a written document that compliments the drawings by filling in the gaps and adding information related to contracts, materials, and methods.

Construction drawings begin where design development drawings end, when all of the major decisions regarding the house design have been made and agreed to. Then the architect engages in the process of drawing everything (within reason) that is necessary to adequately price and construct the house and improve the site. It is a Hurculean effort. In the case of the dinky House drawing set, it was comprised of 26 sheets of 24×36 drawings. That’s pretty typical for our firm’s custom residential projects, although a large house could have twice as many sheets. When dealing with houses, all of the drawings are typically produced by the architect, sometimes with input from other design professionals. Such was the case for the dinky House.

Back in the day, we produced construction drawings, which we called working drawings, on our drawing boards. Using a parallel bar, pencils and pens, we drew and lettered on vellum and mylar. We used scales, compasses, and triangles to produce flat, two dimensional drawings that we enhanced with zip-a -tone and rub-on letters. (I love to draw this way!) This romantic version of the architect was in its last hurrah while I was still in architecture school. By the mid 1980s computers had become sophisticated enough to replace the collection of hand drawing tools…..and quickly did. Computer aided design (CAD) and later, building information modeling (BIM), are now part of virtually every architect’s practice. They are the preferred tool in the construction documents phase due to their accuracy and precision. They are not, at least in my opinion, not the best tool for actually designing, as explained in the schematic design: PART’ TIME post.

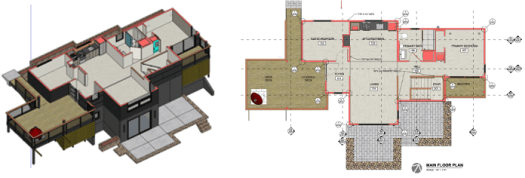

Like most of our firm’s residential projects, the dinky House construction drawings were produced in a modeling program, Sketchup, and its companion program, LayOut. The house was modeled as a 3 dimensional object in SketchUp, then 2 dimensional views were generated in LayOut, where it was fully noted, dimensioned, and rendered. This was done for all of the drawings in the set. The resulting drawings are all to scale with all of the accuracy of the model. The resulting drawings are what the builder used to price and construct the project. Pretty cool, huh?

The order of drawings in the dinky House drawing set is pretty typical. It begins with the site plan, which locates the house on the site and shows the site development. Then come the plans, which are horizontal slices through the house. They include general floor plans, dimensioned floor plans, reflected ceiling plans, and a roof plan. Next, the exterior elevations illustrate what the completed house looks like from every direction. Then come the building sections, which are vertical slices through the house. I have eight cross sections and three longitudinal sections. Interior elevations follow, and illustrate appearance of every wall that is significant in some way, perhaps due to its shape, unique wall finishes, or because they contain cabinetry or built-ins. Next, schedules are included to further describe doors, windows, finish materials, plumbing fixtures, appliances, and toilet accessories. Then there are details, lots of details! Structural drawings come after details and illustrate how the house goes together. They consist of a foundation plan, floor framing plans, and roof framing plans. Unless the house allows for a really simple heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system, I normally provide mechanical plans. (Spoiler alert: the dinky House has a mechanical plan.) Electrical drawings complete the drawing set. They contain power plans and lighting plans for the house and site.

The project manual is the often forgotten part of the construction documents. At least for me, these are not fiil-in-the-blank or boiler plate documents. They are specifically tailored to the house, just as the drawings are. They contain information regarding procurement, a bid form, requirements for the builder and his subs, and technical specifications for virtually every material and system in the house and site. Contractually they carry even more weight than the drawings. Should they be in conflict with the drawings, they take precedence. In the case of the dinky House, I ended up with 41 pages in the project manual, not including the contract. More on that in the next issue.

After the intense effort of the construction documents phase, we are ready to find out what it will actually cost to construct the house, and hopefully engage in the steps to get construction underway. We’ll pick up there in the next issue – procurement: LET’S GO!.

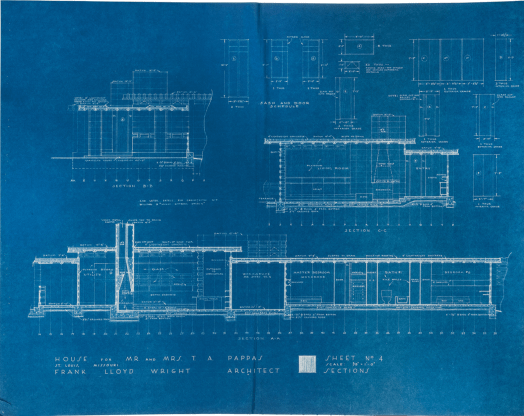

BONUS Material:

Blueprints are the physical sheets of drawings generated using a contact print process that results in blue sheets with white lines. It’s basically a negative image. If you’ve seen original construction drawings by an early 20th century architect, you’ll immediately recognize them as blueprints. Blueprints were the common reprographic technique used back then, but it is an old technique and has long since fallen out of favor. For a while the profession used what were called blue line drawings, or whiteprints – blue lines on white paper. They were easier to read and allowed the architect to make notes directly to them. Most architectural drawings these days are reproduced more like a photocopy – black lines on white paper. Our firm sometimes uses color prints, which I think will become increasing commonplace. It allow us to increased flexibility in how to illustrate our design intent to the client and builder.

Like many words, the definition of blueprint has evolved. What I’ve been describing as construction drawings are just a pumped up version of what many think of as blueprints.. Architects don’t really use the term, unless they are actually referring to a very old drawing that actually is a blueprint. In fact, about the only time we hear blueprint mentioned is when someone is on the phone asking, “How much would you charge me to draw up some blueprints?” …..There are so many things wrong with that question that it’s difficult to know how to begin answering it! Now, perhaps, I can just refer them to weshapespce.com.